Happy Halloween! I have a treat for you today, no tricks!

Franchot starred in an episode of Suspense that aired on October 28, 1952. Filmed live for television, Suspense was a popular mystery-thriller anthology that ran from 1949 to 1954. Each thirty-minute episode dealt with threatening characters and/or situations.

In the episode All Hallow's Eve, Franchot plays Markheim, a seeming sickly middle-aged man in need of money to marry. This episode is set in London in the 1880s and street urchins follow Markheim around hoping for treats. Markheim enters a Victorian pawnshop where he often trades objects for money. When the proprietor insinuates that Markheim is selling him stolen goods, Markheim makes a life-changing decision. What Markheim doesn't know is that there's a devilish creature that's been watching him since birth and this creature has witnessed the entire event.

Fortunately, All Hallow's Eve is available in full-length format on Youtube! If you can't see the embedded video below, click here.

I rewatched All Hallow's Eve first thing this morning to kick off my Halloween and it really is a creepy little tale. I'm sure it was a fun role for Franchot to play, because he's able to be this over-the-top character with big eyes, a looming stature, and gaping fear. Enjoy your day!

Monday, October 31, 2016

Sunday, October 30, 2016

Advise & Consent: Franchot & Politics

When I learned of Pop Culture Reverie's timely Hail to the Chief Blogathon, I knew I had to write about Franchot Tone's portrayal of the fictional U.S. president in Otto Preminger's 1962 drama Advise & Consent. Last costarring with Bing Crosby and Jane Wyman in 1951's Capra film Here Comes the Groom, Advise & Consent marked Franchot's first major studio film in 11 years. (He starred in the independently produced film Uncle Vanya in 1957.) Although he'd been consistently working in television and theatre productions throughout the 50's and 60's, Advise and Consent was touted as Franchot's "comeback" film. Some consider Franchot's presidential performance to be the best of his career. Although I enjoy far too many of Franchot's films to choose only one, I would say it's definitely a top contender.

If one is to have a comeback film, I can't think of a better role or film. Directed by Otto Preminger and written by Wendell Mayes, the censor-breaking film was based on the popular and controversial novel of the same name by Allen Drury. You couldn't dream up a better cast: Lew Ayres is VP and Walter Pidgeon is senate majority leader, Henry Fonda as secretary of state nominee Robert Leffingwell, Charles Laughton as Senator Cooley, Don Murray as Senator Anderson, and Peter Lawford as Senator Smith. Gene Tierney and Meredith Burgess complete the cast in small, but effective roles.

With a runtime of over 2 hours, Advise & Consent is a twisting masterpiece that exposes the complicated relationships between and actions of honest and deceitful members of politics. For the purpose of this post, I am focusing on the treatment of the President and Franchot Tone's portrayal of that character.

As the film opens we see the headline "Leffingwell Picked for Secretary of State" boldly standing out on a newspaper front. This is not only news to the public, but to the senators who had agreed upon a list of suitable candidates for the position. None being Leffingwell, of course.

Senate majority leader Robert Munson (Walter Pidgeon) is on the phone to the president immediately. The president (Franchot Tone), calmly ingesting some pills with his morning coffee at his desk, explains that the former secretary of state has been dead for two weeks and the appointment cannot wait any longer.

"I had to get it done," the president states. When Munson questions his choice of Leffingwell who has "more enemies in congress than anyone in government," the president responds that he knows he's taken a risk, but that he thinks it will result in "creative statemanship."

"Maybe that's why I want him. He doesn't waste his time on trifles."

Opening his speech in front of the White House Correspondents Association, the president astounds everyone when he goes off-script and declares that he will break the standard "No Reporters" rule and encourages reporters to get out their pencils and notepads. Smiling, the president, in highly undiplomatic form, then calls out his opposition Senators Cooley and Anderson. The president states:

After the speech is over, a smiling and swaggering president meets with Anderson and Munson privately. Like a child who knows he's been naughty, but doesn't understand why he everyones taking it so hard, the president smirks at Senator Anderson, "Sore at me, Brigham?"

When Anderson responds that he's merely puzzled, the president confesses that he's angry that Anderson is holding up Leffingwell's confirmation when there are enough votes on the floor to pass him through. A man of principle, Anderson cannot endorse a candidate who lies under oath, and the following exchange occurs:

President: Aren't you interested in why he lied?

Anderson: I'm not completely unsympathetic. I just think that...

President: You think that he should let himself be ruined just because he flirted with Communism a long time ago?

Anderson: But the point is he should've told the committee that he had flirted with communism instead of lying about it on the stand.

President: Well, maybe there's nothing in your young life you'd like to conceal but we're not always that fortunate. We have to make the best of our mistakes. That's all Leffingwell has done. As the leader of our party, I'm asking you. Let me judge the man.

Anderson: Mr. President, I don't want to wreck his life. I don't want to deprive you of his services in some other office. But in this case, his confirmation as secretary of state, I am bound by my duty to my committee.

Anderson: Mr. President, I'm sorry, but your arguments won't wash with me.

President: My prestige is riding on this nomination. The prestige of this country, Senator Anderson. By God, that oughta wash. Or don't you know we're in trouble in the big world outside that little subcommittee of yours?

When Anderson replies that he will not back down, the president, infuriated, storms out of the room.

Again we, the viewers, look to the reliable Robert Munson to settle our feelings about the aggressive and insistent president we've just witnessed. Munson says:

Just minutes after we see the president make his remark that unlike Anderson, most people have actions in their youth that they'd like to keep secret, a blackmailer calls Anderson's home threatening to reveal a past indiscretion. Timing-wise, this couldn't be more perfect. This happens to Anderson directly after being publicly and privately attacked by the president of the United States. You cannot help but wonder whether the president, with his headstrong dedication to the nomination, could be responsible for something so under-handed. As I watched, I continued wondering whether a president, fictional or real, could get away with such a dirty play. *spoiler* Anderson is so desperate to keep a previous same-sex relationship quiet that he is driven to suicide. It's a devastating moment and I remember being stunned the first time I watched the film.

Vice President Harley Hudson and Robert Munson meet with the president on a dark dock to share the tragic news. Munson, again a kind of representative of the viewer throughout the film, must ask what we are all wondering. It's been discovered that a sleazy, manipulative senator Van Ackerman was behind the vicious blackmail of Anderson, but Munson can't help but add, "What I don't know is he alone in it. If he is alone in it, it becomes a senate matter, for the senate to handle in its own way."

The president asks, "And if Van Ackerman isn't alone?" before realizing that the suspicion is being cast on him. The president sees it in Munson and Hudson's eyes. Sees the doubt. Sees the fear. Sees the hurt. And we, in turn, see a genuine reaction from Tone's president. He lets his guard down to express raw disbelief:

The president's pending death is what is driving him to fill this position. He's desperate to continue his legacy, desperate not to lose any of the progress he's made in politics. He knows that Leffingwell is the man to continue the path and doesn't want to risk another man gaining the job.

Urgency is key to Franchot's part in this film. Although the film is lengthy and there are some segments of rather dry dialogue, there is a constant reminder that this decision needs to be made in a hurry. In the first scene featuring the president, he is telling Munson that he's announced the controversial nomination because he "had to get it done." The president wants Leffingwell because he "doesn't waste his time..." And in his final scene with Munson, the president uses a similar hurried vocabulary. Instead of saying, "I'm dying," Tone's character says, "I'm going fast...I haven't any time...I haven't any time for anything...I can't dwell on that."

The president knows he cannot dwell on the reputation he's gained since the Leffingwell announcement. He only knows that he must push the nomination through. It will be his final act as the leader of the country and he knows it. He's a powerful man and does not want to leave the future up to chance. He wants the secretary of state to be his decision, the final decision of his career.

I think you have to realize that this is a man who does not want to be remembered for dying in the middle of his second term. He wants to be remembered as a president who made progress in foreign relations and who paved the way for future progress with his appointment of Leffingwell. This is the last time for the president to define his legacy and make an active decision in power. He is all too aware of the disease conquering his body and he is desperate for one last stand. When you realize this as a viewer, I believe it softens the edges on the stubborn, aggressive politician we see at the correspondents' speech and in the private meeting with Senator Anderson. The urgency to fulfill this last act before leaving his legacy up to the history books is what drives Franchot's president to take such an unorthodox approach. Franchot's president is not a revered leader, but a flesh-and-bone, flawed human being.

*spoiler*Despite all of his efforts and the tragic event that occurs, the president is not able to secure the vote in time. We hear but do not see the president collapse, before the voting on the floor is complete. The eternally put-upon and doubted Harley Hudson, making a bold move as the new president, halts proceedings so that he can choose his own secretary of state.

Here is the official 4 minute-long trailer with a behind-the-scenes look. (If the embedded video doesn't play, click here.)

Film Bulletin called Advise & Consent a film of distinction. It noted that the film would:

Never very kind to Tone as a general rule, New York Times reviewer Bosley Crowther reviewed the "sassy, stinging" film this way:

Thank you for checking out my take on Franchot's U.S. President in Advise & Consent. Please head over to Pop Culture Reverie to read other great posts in the Hail-to-the-Chief Blogathon.

Next up in my own Franchot & Politics series, I'll be covering the 1936 political film The Gorgeous Hussy. Additional posts I've written in my Franchot & Politics series include:

Sources:

"20-Second Trailer Ready on Preminger's 'Advise'." Box Office. August 7, 1961. 17.

"'Advise & Consent' Provocative, Controversial and Good Drama." Film Bulletin. May 28, 1962. 11. "Screen: 'Advise and Consent' Opens:Movie on Washington Is at Two Theatres." The New York Times. June 7, 1962.

If one is to have a comeback film, I can't think of a better role or film. Directed by Otto Preminger and written by Wendell Mayes, the censor-breaking film was based on the popular and controversial novel of the same name by Allen Drury. You couldn't dream up a better cast: Lew Ayres is VP and Walter Pidgeon is senate majority leader, Henry Fonda as secretary of state nominee Robert Leffingwell, Charles Laughton as Senator Cooley, Don Murray as Senator Anderson, and Peter Lawford as Senator Smith. Gene Tierney and Meredith Burgess complete the cast in small, but effective roles.

With a runtime of over 2 hours, Advise & Consent is a twisting masterpiece that exposes the complicated relationships between and actions of honest and deceitful members of politics. For the purpose of this post, I am focusing on the treatment of the President and Franchot Tone's portrayal of that character.

As the film opens we see the headline "Leffingwell Picked for Secretary of State" boldly standing out on a newspaper front. This is not only news to the public, but to the senators who had agreed upon a list of suitable candidates for the position. None being Leffingwell, of course.

Senate majority leader Robert Munson (Walter Pidgeon) is on the phone to the president immediately. The president (Franchot Tone), calmly ingesting some pills with his morning coffee at his desk, explains that the former secretary of state has been dead for two weeks and the appointment cannot wait any longer.

"I had to get it done," the president states. When Munson questions his choice of Leffingwell who has "more enemies in congress than anyone in government," the president responds that he knows he's taken a risk, but that he thinks it will result in "creative statemanship."

"Maybe that's why I want him. He doesn't waste his time on trifles."

From the beginning of the film, we base our opinion on the fictional president (who is never given a surname, but later on in a single moment of the film is addressed as"Russ") on Munson's reactions. Playing the part of the trustworthy, morally-upstanding, and experienced leader, Pidgeon's Munson shows confidence when we should and likewise, expresses doubt when we begin to feel it. When Munson tells another senator that he will support the president all he can, the viewer feels that there's good reason. As Munson briefly pauses and adds "right now," we get a sense that there's an urgency to this support. Munson's reaction lets us know that perhaps this bold, party-splitting decision does not reflect the past actions of the president.

The president expects resistance, but does not foresee the total opposition from a cranky and plotting Senator Steve Cooley (Laughton) and straight-laced, firm Senator Brigham Anderson (Murray). When Cooley exposes communist ties in Leffingwell's past, Anderson heads the subcommittee in its investigation. In front of the committee, Leffingwell (Fonda) commits perjury.

When he reveals his perjury to the president and asks him to withdraw the nomination, the president is visibly stunned. In his role, Franchot's face freezes before he must sit back silently in his seat processing this confession. Realizing action must take place, the president, furiously smoking a cigarette, begins to pace the room. Leffingwell reveals that although he was never a member of the Communist party, he did attend some meetings out of curiosity as a young man. The president is silently pacing as he hears the explanation. The president never asks for more information. He simply asks, "Anybody else know you lied?" and when Leffingwell responds that one person knows the truth, the president with his back to the camera asks, "Will he talk?"

It's evident in the president's response that he's hoping to sweep the entire incident under the rug. Although a political loner, Leffingwell is consistently shown as a typically honest man who lies because he knows that any Communist association can ruin one's career. It is clear that Cooley has uncovered the one and only stain on Leffingwell's reputation. Still firmly believing in Leffingwell, the president refuses to withdraw his nomination. When that one person who knows Leffingwell lied does indeed talk, the president publicly shames Senators Cooley and Anderson in order to prove how strongly he supports his nominee.

Opening his speech in front of the White House Correspondents Association, the president astounds everyone when he goes off-script and declares that he will break the standard "No Reporters" rule and encourages reporters to get out their pencils and notepads. Smiling, the president, in highly undiplomatic form, then calls out his opposition Senators Cooley and Anderson. The president states:

This is your story...The President is standing by his nominee despite Senator Cooley's windstorm and Brigham Anderson's tunneling. You can tell your readers the president hasn't changed his mind about the nominee one fraction of an inch. He's going to fight for that confirmation no matter what.As he literally names Cooley and Anderson the collective Big Bad Wolf, the president sets up a narrative that Leffingwell is the innocent victim. Tone plays this scene with an interesting combination of playfulness and complete menace. He charmingly grins as he pretty much declares a personal war against the senators who disagree with him.

After the speech is over, a smiling and swaggering president meets with Anderson and Munson privately. Like a child who knows he's been naughty, but doesn't understand why he everyones taking it so hard, the president smirks at Senator Anderson, "Sore at me, Brigham?"

When Anderson responds that he's merely puzzled, the president confesses that he's angry that Anderson is holding up Leffingwell's confirmation when there are enough votes on the floor to pass him through. A man of principle, Anderson cannot endorse a candidate who lies under oath, and the following exchange occurs:

President: Aren't you interested in why he lied?

Anderson: I'm not completely unsympathetic. I just think that...

President: You think that he should let himself be ruined just because he flirted with Communism a long time ago?

Anderson: But the point is he should've told the committee that he had flirted with communism instead of lying about it on the stand.

President: Well, maybe there's nothing in your young life you'd like to conceal but we're not always that fortunate. We have to make the best of our mistakes. That's all Leffingwell has done. As the leader of our party, I'm asking you. Let me judge the man.

Anderson: Mr. President, I don't want to wreck his life. I don't want to deprive you of his services in some other office. But in this case, his confirmation as secretary of state, I am bound by my duty to my committee.

Anderson: Mr. President, I'm sorry, but your arguments won't wash with me.

President: My prestige is riding on this nomination. The prestige of this country, Senator Anderson. By God, that oughta wash. Or don't you know we're in trouble in the big world outside that little subcommittee of yours?

When Anderson replies that he will not back down, the president, infuriated, storms out of the room.

Again we, the viewers, look to the reliable Robert Munson to settle our feelings about the aggressive and insistent president we've just witnessed. Munson says:

I guess it is inconsistent, but I've come along way with him ever since we were green congressmen together. He's pulled us through 6 hard years of crisis. He's tired, Brig, and he's ill. I love the man. I guess I can stretch my responsibility a little, enough to help him.Munson's affirmation that the president hasn't always been such an unpliable leader, that this behavior is not common for him, and that he is unwell make the president a more sympathetic character.

Just minutes after we see the president make his remark that unlike Anderson, most people have actions in their youth that they'd like to keep secret, a blackmailer calls Anderson's home threatening to reveal a past indiscretion. Timing-wise, this couldn't be more perfect. This happens to Anderson directly after being publicly and privately attacked by the president of the United States. You cannot help but wonder whether the president, with his headstrong dedication to the nomination, could be responsible for something so under-handed. As I watched, I continued wondering whether a president, fictional or real, could get away with such a dirty play. *spoiler* Anderson is so desperate to keep a previous same-sex relationship quiet that he is driven to suicide. It's a devastating moment and I remember being stunned the first time I watched the film.

Vice President Harley Hudson and Robert Munson meet with the president on a dark dock to share the tragic news. Munson, again a kind of representative of the viewer throughout the film, must ask what we are all wondering. It's been discovered that a sleazy, manipulative senator Van Ackerman was behind the vicious blackmail of Anderson, but Munson can't help but add, "What I don't know is he alone in it. If he is alone in it, it becomes a senate matter, for the senate to handle in its own way."

The president asks, "And if Van Ackerman isn't alone?" before realizing that the suspicion is being cast on him. The president sees it in Munson and Hudson's eyes. Sees the doubt. Sees the fear. Sees the hurt. And we, in turn, see a genuine reaction from Tone's president. He lets his guard down to express raw disbelief:

Is that what they think of me on the Hill? Is that what you think of me, Bobby? As God as my witness, Harley, I know nothing.When Munson relaxes after witnessing the president's candid reaction, we know that we can stop wondering about it, too. When he warns that suspicion may arise if he immediately promotes Leffingwell, Tone's character responds:

The president is always suspect in some quarters because people are suspicious of power. Can't be chided by that. I'm sorry about Brig Anderson. Don't misunderstand me. I wish he were alive and happy. He's dead. Morning's coming and I still need a secretary of state. The situation hasn't changed except now you can bring Leffingwell to the floor for a vote. You've got the votes committed, Bobby. Use them.After he dismisses the Vice President (everyone dismisses the kind, disrespected VP throughout the film, but that's a post for another blogger to tackle), the president turns to Munson with an unexpected confession:

Bobby? I do want to confirm a suspicion to you. Maybe it'll help you understand why I want Leffingwell so badly... I'm going fast. Nothing left inside here that's working anymore. Leffingwell can take a firm grip on everything I've built up in foreign policy. Not let it all fall to pieces. Harley can't. You know he can't...I haven't any time to run a school for presidents! I haven't any time for anything. I guess I've been wrong in many, many things. I don't suppose history will have much good to say of me. I can't dwell on that. I've done my best.To this vulnerable intimation, Munson sincerely replies:

You're one of the great presidents, Russ.

The president's pending death is what is driving him to fill this position. He's desperate to continue his legacy, desperate not to lose any of the progress he's made in politics. He knows that Leffingwell is the man to continue the path and doesn't want to risk another man gaining the job.

Urgency is key to Franchot's part in this film. Although the film is lengthy and there are some segments of rather dry dialogue, there is a constant reminder that this decision needs to be made in a hurry. In the first scene featuring the president, he is telling Munson that he's announced the controversial nomination because he "had to get it done." The president wants Leffingwell because he "doesn't waste his time..." And in his final scene with Munson, the president uses a similar hurried vocabulary. Instead of saying, "I'm dying," Tone's character says, "I'm going fast...I haven't any time...I haven't any time for anything...I can't dwell on that."

The president knows he cannot dwell on the reputation he's gained since the Leffingwell announcement. He only knows that he must push the nomination through. It will be his final act as the leader of the country and he knows it. He's a powerful man and does not want to leave the future up to chance. He wants the secretary of state to be his decision, the final decision of his career.

I think you have to realize that this is a man who does not want to be remembered for dying in the middle of his second term. He wants to be remembered as a president who made progress in foreign relations and who paved the way for future progress with his appointment of Leffingwell. This is the last time for the president to define his legacy and make an active decision in power. He is all too aware of the disease conquering his body and he is desperate for one last stand. When you realize this as a viewer, I believe it softens the edges on the stubborn, aggressive politician we see at the correspondents' speech and in the private meeting with Senator Anderson. The urgency to fulfill this last act before leaving his legacy up to the history books is what drives Franchot's president to take such an unorthodox approach. Franchot's president is not a revered leader, but a flesh-and-bone, flawed human being.

*spoiler*Despite all of his efforts and the tragic event that occurs, the president is not able to secure the vote in time. We hear but do not see the president collapse, before the voting on the floor is complete. The eternally put-upon and doubted Harley Hudson, making a bold move as the new president, halts proceedings so that he can choose his own secretary of state.

The Novel

I have not read the original Advise & Consent novel on which the movie was based. However, from what I've read about the book, the president within its pages is implicated in the blackmail scheme. In the book, apparently the president supplies Van Ackerman a damning photo of Anderson. It is explained that the president doesn't think that Van Ackerman will actually use it and does not expect Anderson's reaction to it. None of this happens in the film version unless we are being unknowingly led, by the president's convincing denial and Munson's steadfast support, to believe differently. (Although I did think the first call to Anderson's house sounded a bit like Franchot's gravelly voice, so you can sleuth it out and see if I've completely been duped by the fictional president and his friend Bobby Munson!)Response to the Film

Preminger designed a 20-second color theatrical trailer for Advise & Consent to be shown at screenings of his film Exodus. According to Box Office Magazine, pre-production work had just begun so this was the first instance of a theatrical trailer being released far in advance of a release date.Here is the official 4 minute-long trailer with a behind-the-scenes look. (If the embedded video doesn't play, click here.)

Film Bulletin called Advise & Consent a film of distinction. It noted that the film would:

anger some, please others, intrigue all. It has been unfolded in an intelligent, informative, and engrossing manner, and thanks to Preminger's skill as a film maker, the bold aspects have been presented with good taste and reasonable consideration of the national welfare...What makes 'Advise and Consent' so noteworthy is that its solid dramatic merits actually overshadow the many controversial aspects. Movies dealing with political life usually have leaned toward the bizarre and bombastic. This does not. It has a quality of seeming factuality and dramatic validity.The Bulletin singled out Franchot's lifelong friends Charles Laughton and Burgess Meredith for their performances and noted that Franchot gave a "fine delination" as the "strong-willed, seriously ill President."

Never very kind to Tone as a general rule, New York Times reviewer Bosley Crowther reviewed the "sassy, stinging" film this way:

Mr. Preminger and Wendell Mayes, his writer, taking their cue from Mr. Drury's book, have loaded their drama with rascals to show the types in Washington. Their intense and deliberate projection of a cynical attitude toward the actions of politicians extends right up to the President of the United States, whom they frankly portray in this fiction as a man of peculiar principles. He is made (in a tasteless portrayal of a sick, testy man by Franchot Tone) to be tolerant of cheap conniving and the telling of lies under oath.Weeks ago, I was researching this topic in old magazine and newspaper articles, and I came across a mention of Franchot's pride in the film. The article said that Franchot was so proud of Advise & Consent that he flew in his two sons to an early screening of it. Unfortunately, I was in a hurry and didn't save the article. I've tried duplicating my search, but no luck so far.

Thank you for checking out my take on Franchot's U.S. President in Advise & Consent. Please head over to Pop Culture Reverie to read other great posts in the Hail-to-the-Chief Blogathon.

Next up in my own Franchot & Politics series, I'll be covering the 1936 political film The Gorgeous Hussy. Additional posts I've written in my Franchot & Politics series include:

Sources:

"20-Second Trailer Ready on Preminger's 'Advise'." Box Office. August 7, 1961. 17.

"'Advise & Consent' Provocative, Controversial and Good Drama." Film Bulletin. May 28, 1962. 11. "Screen: 'Advise and Consent' Opens:Movie on Washington Is at Two Theatres." The New York Times. June 7, 1962.

Saturday, October 22, 2016

A Political Ancestry: Franchot & Politics

For this week's (belated) entry into my Franchot & Politics series, I'd like to share with you some biographical sketches on the political figures of Franchot's maternal family. Franchot's grandfather and great grandfather held Republican seats in the Senate and Congress, respectively. Franchot's mother was a progressive liberal who fought for women's equality and was an anti-war activist. Franchot's uncles also had political positions.

Note: Since Franchot is the given name of the main subject of this blog and the surname of his ancestors, I will avoid confusion by using Franchot Tone's ancestors given names. Also, Franchot Tone's full name was Stanislaus Pascal Franchot Tone, a name passed down through generations. In some sources, I've seen Pascal spelled as Paschal. For the purposes of this blog, I am going to stick with the spelling that Franchot Tone used: Pascal.

Richard Hansen Franchot (1816-1875)-Franchot's Great Grandfather

Born in Otsego County, New York in 1816, Richard Franchot was the well-educated son of French emigrant Stanislaus Pascal Franchot. A civil engineer, Richard was engaged in mercantile and manufacturing before becoming a member of the Thirty-seventh Congress, representing the Nineteenth District of New York from 1861 to 1863. He had also served as a general in the U.S. Volunteers.

His business and civil engineering interests led Richard to help form the New York Central railroad and become an important member of the Pacific Railroad Committee. After leaving Congress, Richard was hired by railroad magnate Collis Huntington to lobby Congress to enact legislation that would support the Central Pacific. Author Stephen E. Ambrose, in his book Nothing Like It in the World, suggests that Richard Franchot was more than likely the first paid lobbyist and that he made quite a lot of money in this new role.

This description of Richard in Notable Men in the House is reminiscent of some comments I've read about his great grandson Franchot:

Stanislaus Pascal Franchot, often referred to in print as S.P., was the son of Congressman Richard H. Franchot. A civil engineer by education, S.P. was involved in lumber, oil producing, mining, and chemical businesses. He patented an electrolyte process for manufacturing and managed the National Electrolyte Company. A police commissioner in Niagara Falls in the early 1900's, S.P. was elected to the State Senate, representing the Forty-seventh Senate District, in 1906.

S.P.'s brother Nicholas Van Vranken Franchot (1855-1943) was a delegate to the Republican National Convention in the 1890's and in 1905, was appointed New York State Superintendent of Public Works. N.V.V. Franchot also served as mayor of Olean, New York.

S.P.'s children were Edward Eells Franchot, Nicholas Van Vranken Franchot II, and Gertrude Van Vranken Franchot (Franchot Tone's mother.)

S.P. passed down the political involvement he had acquired from his father Richard. Son Edward was a delegate to the New York State Constitutional Convention and son Nicholas was a member of the New York State Assembly.

Gertrude Van Vranken Franchot Tone (1876-1953)-Franchot's Mother

I've read that when Franchot was in NYC he would avoid dining at restaurants where his mother publicly crusaded. I don't know if that's true or not. Gertrude certainly seemed to live an interesting personal and political life (I requested some additional books that mention Gertrude, but they did not arrive at my library in time for this post.) Franchot contributed to many war relief organizations and sold war bonds during World War II, so I wonder if, given his mother's formal affirmation to the WPU, Franchot's support caused any minor or major rift with Gertrude. It would seem to me that Gertrude would've disliked Franchot's role as a WWII pilot in Pilot No. 5, but liked his non-fighting pacifist in The Hour Before the Dawn.

Franchot Tone and the Screen Actors' Guild

As you can see, Franchot Tone came from a long line of politicians and political activists. The Franchot family was involved in many historic American moments. Richard Franchot helped form and support the Transcontinental Railroad and his granddaughter Gertrude fought for women's right to vote. Franchot must have been shaped by his ancestors' political history. By pursuing a career as an actor, Franchot broke the chain of political positions, but never abandoned his well-versed knowledge in political history and support of social causes. Many of his films and plays take place in a political setting or take on political issues. Also, Franchot was active in the Screen Actors' Guild.

In 1937, Franchot joined the negotiating committee of the Screen Actors' Guild and fought (and succeeded) to get the Guild officially recognized by studio heads. He served as a prominent board member of SAG until the following by-law was passed in 1946:

Next week, I'll be covering the 1962 Preminger film Advise & Consent, in which Franchot plays the president, for Pop Culture Reverie's Hail to the Chief Blogathon. Additional posts I've written in my Franchot & Politics series include:

Sources:

Note: Since Franchot is the given name of the main subject of this blog and the surname of his ancestors, I will avoid confusion by using Franchot Tone's ancestors given names. Also, Franchot Tone's full name was Stanislaus Pascal Franchot Tone, a name passed down through generations. In some sources, I've seen Pascal spelled as Paschal. For the purposes of this blog, I am going to stick with the spelling that Franchot Tone used: Pascal.

Richard Hansen Franchot (1816-1875)-Franchot's Great Grandfather

|

| Richard Hansen Franchot, Franchot Tone's great grandfather. Source: www.geni.com |

His business and civil engineering interests led Richard to help form the New York Central railroad and become an important member of the Pacific Railroad Committee. After leaving Congress, Richard was hired by railroad magnate Collis Huntington to lobby Congress to enact legislation that would support the Central Pacific. Author Stephen E. Ambrose, in his book Nothing Like It in the World, suggests that Richard Franchot was more than likely the first paid lobbyist and that he made quite a lot of money in this new role.

This description of Richard in Notable Men in the House is reminiscent of some comments I've read about his great grandson Franchot:

And notwithstanding his quiet ways and unpretending manners, he was well known in the political canvasses of those days as an intelligent and effective platform-champion of his party. Although born and bred a gentleman, and accustomed from infancy to the most refined and elevating associations, he early learned to know and appreciate the great, true heart of the masses, and the people loved him; and in this was the mighty secret of his political success and power.Stanislaus Pascal Franchot (1851-1908)-Franchot's Grandfather

|

| Stanislaus P. Franchot, Franchot Tone's grandfather. Source: National Library of Canada. |

S.P.'s brother Nicholas Van Vranken Franchot (1855-1943) was a delegate to the Republican National Convention in the 1890's and in 1905, was appointed New York State Superintendent of Public Works. N.V.V. Franchot also served as mayor of Olean, New York.

S.P.'s children were Edward Eells Franchot, Nicholas Van Vranken Franchot II, and Gertrude Van Vranken Franchot (Franchot Tone's mother.)

S.P. passed down the political involvement he had acquired from his father Richard. Son Edward was a delegate to the New York State Constitutional Convention and son Nicholas was a member of the New York State Assembly.

Gertrude Van Vranken Franchot Tone (1876-1953)-Franchot's Mother

|

| Gertrude Franchot Tone, Franchot's mother. Source:The New Movie Magazine. |

Like her father and grandfather before her, Gertrude Franchot was passionate about politics. Unlike the male Franchots, however, Gertrude was a progressive liberal who was an early champion for women's rights.

Gertrude led the Suffragists' State Convention in 1917. Involved in the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom in 1915, Gertrude was a key member during the formation of the Women's Peace Society in 1919. Gertrude became an active member and served as treasurer of the new Women's Peace Union of the Western Hemisphere in the 1920's. According to a letter the union submitted to The Nation in 1921, members differentiated the two groups in this manner: The Women's Peace Society focused on education while the new Women's Peace Union would work on "political and economic lines." To join the Women's Peace Union, Gertrude made the following affirmation:

I affirm it is my intention never to aid in or sanction war, offensive or defensive, international or civil, in any way, whether by making or handling munitions, subscribing to war loans, using my labor for the purpose of setting others free for war service, helping by money or work any relief organization which supports or condones war.Not content to be the stay-at-home wife of wealthy businessman Frank J. Tone, Gertrude welcomed WPU-related travel to Washington, D.C. and New York City. A financial advisor for the union, Gertrude was often in charge of lobbying for the group.

I've read that when Franchot was in NYC he would avoid dining at restaurants where his mother publicly crusaded. I don't know if that's true or not. Gertrude certainly seemed to live an interesting personal and political life (I requested some additional books that mention Gertrude, but they did not arrive at my library in time for this post.) Franchot contributed to many war relief organizations and sold war bonds during World War II, so I wonder if, given his mother's formal affirmation to the WPU, Franchot's support caused any minor or major rift with Gertrude. It would seem to me that Gertrude would've disliked Franchot's role as a WWII pilot in Pilot No. 5, but liked his non-fighting pacifist in The Hour Before the Dawn.

Franchot Tone and the Screen Actors' Guild

As you can see, Franchot Tone came from a long line of politicians and political activists. The Franchot family was involved in many historic American moments. Richard Franchot helped form and support the Transcontinental Railroad and his granddaughter Gertrude fought for women's right to vote. Franchot must have been shaped by his ancestors' political history. By pursuing a career as an actor, Franchot broke the chain of political positions, but never abandoned his well-versed knowledge in political history and support of social causes. Many of his films and plays take place in a political setting or take on political issues. Also, Franchot was active in the Screen Actors' Guild.

In 1937, Franchot joined the negotiating committee of the Screen Actors' Guild and fought (and succeeded) to get the Guild officially recognized by studio heads. He served as a prominent board member of SAG until the following by-law was passed in 1946:

no actor or actress who becomes a motion picture producer or director and who, in the judgment of the Board of Directors after a hearing and full examination of the facts, is found to have primarily and continually the interest of an employer, rather than that of an actor, shall hold office in the Screen Actors Guild.Once this resolution was passed, Franchot, James Cagney, Dick Powell, Robert Montgomery, John Garfield, Harpo Marx, and Dennis O'Keefe all resigned. Since the resigned Robert Montgomery had been long-time president, the board of directors held a secret vote and replaced Montgomery with future U.S. president Ronald Reagan.

Next week, I'll be covering the 1962 Preminger film Advise & Consent, in which Franchot plays the president, for Pop Culture Reverie's Hail to the Chief Blogathon. Additional posts I've written in my Franchot & Politics series include:

Sources:

- Alonso, Harriet Hyman. The Women's Peace Union and the Outlawry of War, 1921-1942. Syracuse University Press, 1989.

- Ambrose, Stephen E. Nothing Like It In the World: The Men Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad 1863-1869. Simon and Schuster, 2000.

- "Franchot Family of New York." Political Graveyard. www.politicalgraveyard.com/families/18090.html

- Glyndon, Howard. Notable Men in the House: A series of sketches of prominent men in the House of Representatives, members of the Thirty-seventh Congress. Baker & Godwin, 1862.

- Greiner, James. Subdued by the Sword: A Line Officer in the 121st New York Volunteers. SUNY Press, 2012.

- Guide to the Mary E. Gawthorpe Papers. The Taminent Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives. http://dlib.nyu.edu/findingaids/html/tamwag/tam_275/

- Hills, Frederick Simon. New York State Men: Biographical Studies and Character Portraits. Argus Company, 1910.

- Hoffman, Ethel. "Pamp Tone Makes Good." The New Movie Magazine. October 1934. 54-55.

- Hubbard, John T. and James W. Geary. Biographical Dictionary of the Union: Northern Leaders of the Civil War. Greenwood Publishing Group, 1995.

- Richard Hansen Franchot Genealogy. https://www.geni.com/people/Brevet-Brig-General-Richard-Franchot-USA/6000000012697659426

- Screen Actors' Guild Timeline: 1930's. http://www.sagaftra.org/sag-timeline-1930s

- Screen Actors' Guild Timeline: 1940's. http://www.sagaftra.org/sag-timeline-1940s

- "The Women's Peace Union of the Western Hemisphere." The Nation. September 21, 1921. 321.

Friday, October 14, 2016

Franchot Targeted in the Blacklist: Franchot & Politics

I think all classic film enthusiasts have some knowledge about the powerful and predatory House Un-American Activities Committee that used public threats and scare tactics to terrorize the film industry. It would be denounced by former President Truman in the late 50's and lose its control in the 60's. But by the end of McCarthy era, the damage had already been done. Due to the spiteful insinuations of the committee's public witch hunt, many in the film industry were never able to work again. Although Franchot cleared his name in front of the Dies Committee as early as 1940, an interrogation of anti-communist leader Vincent Hartnett would reveal that Franchot Tone continued to feel the pressure of the blacklist throughout his television career of the 1950's and 60's.

Franchot preferred to work in plays with messages about the human condition and state of the world. He was always most proud of his early association with the Group Theatre, a group of idealistic and educated thespians, playwrights, and directors who valued scripts with artistic integrity, realism, and truth. Like Franchot, many Group Theatre veterans (most famously and tragically, John Garfield) were investigated in some capacity by the House Un-American Activities Committee for their liberal views by the 1950's.

In 1938, conservative congressman Martin Dies relocated to Los Angeles to sniff out communists hiding in the entertainment industry. By 1940, Communist Party organizer John Leech had provided a list of actors he associated with leftist ideas. Among others, the list included: Humphrey Bogart, Fredric March, Franchot Tone, James Cagney, Luise Rainer, Francis Lederer, and Jean Muir. Dies vowed that all named actors would be cleared if they would appear at a hearing before the Dies Committee. If the named actors did not agree to a meeting, Dies announced he would find them guilty of anti-American activity.

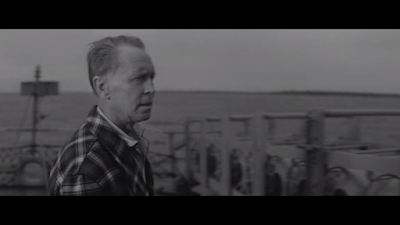

The above photo appeared in newspapers across the county in August 1940. The caption that accompanied it read, "Movie actor Franchot Tone (right) is shown being sworn in by Representative Martin Dies (Dem., Texas) (left) at special hearing before house committee investigating un-American activities at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel in New York. Tone was exonerated at the hearing, which was held yesterday." Further investigation reveals that actress Luise Rainer and actor Francis Lederer were also cleared with Franchot of being communist sympathizers. Martin Dies, the committee representative, noted that although the three actors had allowed their "names to be used or have contributed money" to what the committee deemed communist-led organizations, no evidence existed that their "cooperation was for any purpose except humanitarian." When questioned about his support of needy causes, Franchot was reported to have defended himself by saying, "You see, when you have so much money thrown in your lap, your conscience is aroused."

Still, in 1949, Franchot was listed as one of "Stalin's Stars" in the Red Treason in Hollywood published by Myron C. Fagan. Also accused were Franchot's past costars Bette Davis, Melvyn Douglas, Katharine Hepburn, Gene Kelly, and Sylvia Sidney. In his 1963 book Fear on Trial, author John Henry Faulk includes a transcript of attorney Louis Nizer's interrogation of Vincent Hartnett. Faulk was a humorist who was publicly accused of communist activity by Hartnett after he staunchly opposed Hartnett's right-wing organization AWARE, Inc. Hartnett's organization specialized in blacklisting entertainers and was successful in the blacklisting of Faulk from 1957 to 1962. As early as 1956, Faulk took legal action against Hartnett's libel. The trial did not begin until 1962, at which time Faulk was vindicated and awarded damages. In the court testimony provided by Faulk, I learned that Franchot was being quietly, but actively blacklisted throughout the 1950's. During the trial, attorney Nizer asked Hartnett if he had written to Laurence Johnson (AWARE, Inc. cofounder) about Franchot. Here's the revealing exchange:

Several of Franchot's ancestors were prominent Republican politicians and his mother was an outspoken member of women's liberal groups, so Franchot was well-versed in both the conservative and liberal views. (Next week's post will be on the impressive political careers of Franchot's maternal family.) In an interview with Andre Soares on Alt Film Guide, Tone researcher Lisa Burks commented on Franchot's belief in the democratic process, his eagerness to help families in need, and his family background. You can read that full interview here.

During the blacklist, Franchot felt compelled to help other professionals in need. Anonymously, Franchot supported blacklisted screenwriters who were no longer able to gain employment. Screenwriter Ring Lardner, Jr. worked under a pseudonym when Franchot hired him "out of conviction." Lardner, Jr. recalled, in Tender Comrades and Dark History of Hollywood:

With a heart for humanity and the wealth to support others in need, Franchot defended himself in front of the Dies Committee and, years later, the FBI. In the process, he never sacrificed his colleagues and never abandoned his convictions.

If you'd like to read more about the Hollywood blacklist, please see my sources below. For other posts in the Franchot & Politics series, click here. Stay tuned for next Friday's entry into the series!

Sources:

Franchot preferred to work in plays with messages about the human condition and state of the world. He was always most proud of his early association with the Group Theatre, a group of idealistic and educated thespians, playwrights, and directors who valued scripts with artistic integrity, realism, and truth. Like Franchot, many Group Theatre veterans (most famously and tragically, John Garfield) were investigated in some capacity by the House Un-American Activities Committee for their liberal views by the 1950's.

In 1938, conservative congressman Martin Dies relocated to Los Angeles to sniff out communists hiding in the entertainment industry. By 1940, Communist Party organizer John Leech had provided a list of actors he associated with leftist ideas. Among others, the list included: Humphrey Bogart, Fredric March, Franchot Tone, James Cagney, Luise Rainer, Francis Lederer, and Jean Muir. Dies vowed that all named actors would be cleared if they would appear at a hearing before the Dies Committee. If the named actors did not agree to a meeting, Dies announced he would find them guilty of anti-American activity.

|

| Source: Spokane Daily Chronicle. August 28, 1940. |

|

| Source: Motion Picture Herald headline. August 24, 1940. |

Nizer: What were you writing to Mr. Laurence Johnson with respect to Mr. Franchot Tone? Will you reconstruct that for us?

Hartnett: As best I recall, he had probably asked me for a report on Franchot Tone, which I furnished him; and I believe I had made inquiry to see if Franchot Tone had offset his past record, and had been told he had not done so, at least my source of information. Yet, as best I recall, I expressed an opinion that Franchot Tone should do more than—

Nizer: Before he could appear on television?

Bolan: I object.

Nizer: He should do more before he could appear—he should appear or be allowed to appear on television? Isn't that the substance of it?

Hartnett: Before he was allowed to appear on television?

Nizer: Yes.

Hartnett: Could be. I am not sure of that.

Nizer: Could be. Did you ever write to him, 'if he refused to take a public stand, then we can take the necessary measures?' Did you ever write that to Laurence Johnson?

Hartnett: Yes, that sounds right.

Nizer: 'We' in that case is you and Laurence Johnson, right?

Hartnett: It would seem so...

Nizer: So you asked groups, various individuals to write protests to try to get people off the air that in your opinion had pro-communist affiliation; right?

Hartnett: Yes, I did.As you can read, Hartnett admits to a directed attack of Franchot and his career in the 1950's. As early as 1934, Franchot's political ties were publicly questioned when columnist Walter Winchell reported that Franchot Tone was the only major film actor who had refused to contribute money to the Republican campaign fund, despite strong demands and pressure to do so.

Several of Franchot's ancestors were prominent Republican politicians and his mother was an outspoken member of women's liberal groups, so Franchot was well-versed in both the conservative and liberal views. (Next week's post will be on the impressive political careers of Franchot's maternal family.) In an interview with Andre Soares on Alt Film Guide, Tone researcher Lisa Burks commented on Franchot's belief in the democratic process, his eagerness to help families in need, and his family background. You can read that full interview here.

During the blacklist, Franchot felt compelled to help other professionals in need. Anonymously, Franchot supported blacklisted screenwriters who were no longer able to gain employment. Screenwriter Ring Lardner, Jr. worked under a pseudonym when Franchot hired him "out of conviction." Lardner, Jr. recalled, in Tender Comrades and Dark History of Hollywood:

I had to go into a bank in Beverly Hills where Franchot Tone withdrew $10,000 in cash and gave it to me.Knowing now just how targeted Franchot was by Hartnett, I realize how fortunate Franchot was to survive the blacklist. I can't imagine having those classic Twilight Zone, Bonanza, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, and Ben Casey episodes without Franchot's unique and memorable performances in them. It is clear, through the Faulk case testimony, that Franchot was denied many other opportunities in the 1950's.

With a heart for humanity and the wealth to support others in need, Franchot defended himself in front of the Dies Committee and, years later, the FBI. In the process, he never sacrificed his colleagues and never abandoned his convictions.

If you'd like to read more about the Hollywood blacklist, please see my sources below. For other posts in the Franchot & Politics series, click here. Stay tuned for next Friday's entry into the series!

Sources:

- Ceplair, Larry, and Steven Englund. The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics in the Film Community, 1930-1960. Garden City, NY: Anchor/Doubleday, 1980. Print.

- Connolly, Kieron. Dark History of Hollywood: A Century of Greed, Corruption, and Scandal behind the Movies. London: Amber, 2014. Print.

- Faulk, John Henry. Fear on Trial. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1964. Print.

- "It Seems to Me." Pittsburgh Press. October 29, 1934.

- McGilligan, Patrick, and Paul Buhle. Tender Comrades: A Backstory of the Hollywood Blacklist. New York: St. Martin's, 1997.

- Morgan, Ted. Reds: McCarthyism in Twentieth-century America. New York: Random House, 2004. Print.Print.

- Radosh, Ronald, and Allis Radosh. Red Star over Hollywood: The Film Colony's Long Romance with the Left. San Francisco: Encounter, 2005. Print.

- "Screen Players Freed of Charge." Evening Independent. August 28, 1940.

- Slide, Anthony. Actors on Red Alert: Career Interviews with Five Actors and Actresses Affected by the Blacklist. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow, 1999. Print.

- Smith, Wendy. Real Life Drama: The Group Theatre and America, 1931-1940; New York: Knopf, 1990.

- "Wirephoto: Dies Committee Clears Actor Franchot Tone of Red Charges." Spokane Daily Chronicle. August 28, 1940.

- Slate:http://www.slate.com/articles/podcasts/you_must_remember_this/2016/02/the_origins_of_the_hollywood_blacklist.html

- University of Texas: https://www.lib.utexas.edu/taro/utcah/01497/cah-01497.html

- Alt Film Guide: http://www.altfg.com/film/franchot-tone-lisa-burks/

Friday, October 7, 2016

Gabriel Over the White House (1933): Franchot and Politics

For this week's entry into my Franchot and Politics series, I'm looking at one of Franchot Tone's earliest films, Gabriel Over the White House. Directed by Gregory La Cava and produced by Walter Wanger, the political pre-code stars Walter Huston, Franchot Tone, and Karen Morley.

Gabriel Over the White House begins on President Judd Hammond's first night in the White House. After being congratulated by other members of his party, Hammond (Walter Huston) is approached by his young nephew Jimmy (Dickie Moore) who is excited that his uncle will "cure" the depression and make America rich again. President Hammond worries about fulfilling the many promises he made to get elected to which a fellow official remarks, "By the time they realize you didn't keep them, your term will be over!"

Franchot Tone is Secretary Hartley Beekman or Beek as the president (who in turn insists on being called Major) calls him. Along with his official secretary, Hammond also takes on a personal secretary Pendola Molloy (Karen Morley). It is unclear what Hammond and Molloy's connection is, but they seem to have had a past.

From the start, it is obvious that President Hammond does not plan to make any waves in his new position. When asked about the rampant unemployment and racketeering in America, Hammond dismisses these issues as "local problems" and makes general promises of future prosperity to the public. When Pendola "Penny" tells her boss that he can do great things with the pen he is using, Hammond calls her an idealist and explains, "See, Penny, the party has a plan. I'm just a member of that party."

There's this really great scene where President Hammond is playing with his nephew in the White House. They're searching around and having such fun and are completely oblivious to the booming voice of John Bronson, the leader of the Army of the Unemployed, on the radio who is publicly pleading with the president to take action. This scene really hits home just how purposeless Judd intends to be as a leader. Shortly after, the carefree president is speeding in his car, trying to push it to 110 miles per hour, when he crashes it and loses consciousness.

Here's where the film takes a strange turn. While he's unconscious, divine intervention occurs. Penny is later convinced this divine intervention is angel Gabriel sent as a messenger from God to President Hammond. Suddenly, Judd Hammond is a changed man. He talks with purpose and actively seeks out meetings with the unemployed and racketeers. He wants to feed, clothe, and shelter the poor. He wants to punish the racketeers. This is all wonderful progress, for sure.

However, when Congress, the Senate, and the Cabinet all question him, the President requests the resignation of all the men who put him in power. Hammond then declares a state of emergency giving him full dictatorship. Hammond declares that he wants to be a dictator for the greater good, but I think most of us can agree that a man, without any checks and balances of any kind, who has sole power over a nation can be a very frightening prospect. In this film, Hammond is able to kill gangsters execution-style because he believes in an eye-for-an-eye. He bombs a ship to show how peace is needed in the world. Hammond certainly has the right ideals, but he gives himself such a position that denies citizens their right to a democracy. In the end, we see that an ailing President Hammond, a hero in the eyes of the public, has initiated the Washington Covenant, a signed treaty across nations, to ensure peace and prosperity for all.

As the film progresses, Franchot's character Beekman develops feelings for Penny and continues to idolize Hammond. When he appoints himself as dictator, Hammond changes Beekman's position of secretary to the President to secretary of war. It's not a large role for Franchot, but it has substance to it and he plays it well.

It's definitely an interesting treatment of politics in film. Because of its turn from democracy to dictatorship, this pre-code film is controversial to today's audience. Watching it, I grew uncomfortable when Hammond declared himself a dictator and obtained full control. Thankfully, he used his power for eventual good, but I was not in agreement with his ways of getting to that final peace agreement. I was astounded when Hammond ordered the execution of the racketeering gang and Beekman oversaw these orders. The scene played like one gang's retaliation on another gang, not a just and fair President's actions. Although I and many other current viewers have some reservations about the film's direction, audiences in 1933 loved the film's message. Desperate for a solution to the depression, hopeful about President Roosevelt, and eager for active change, Gabriel Over the White House was praised by viewers as an "inspiration" and "what the whole world is praying for."

Photoplay Magazine readers wrote letters praising the film.

Marshall Mills of Massachusetts wrote:

Sources:

Gabriel Over the White House begins on President Judd Hammond's first night in the White House. After being congratulated by other members of his party, Hammond (Walter Huston) is approached by his young nephew Jimmy (Dickie Moore) who is excited that his uncle will "cure" the depression and make America rich again. President Hammond worries about fulfilling the many promises he made to get elected to which a fellow official remarks, "By the time they realize you didn't keep them, your term will be over!"

Franchot Tone is Secretary Hartley Beekman or Beek as the president (who in turn insists on being called Major) calls him. Along with his official secretary, Hammond also takes on a personal secretary Pendola Molloy (Karen Morley). It is unclear what Hammond and Molloy's connection is, but they seem to have had a past.

From the start, it is obvious that President Hammond does not plan to make any waves in his new position. When asked about the rampant unemployment and racketeering in America, Hammond dismisses these issues as "local problems" and makes general promises of future prosperity to the public. When Pendola "Penny" tells her boss that he can do great things with the pen he is using, Hammond calls her an idealist and explains, "See, Penny, the party has a plan. I'm just a member of that party."

There's this really great scene where President Hammond is playing with his nephew in the White House. They're searching around and having such fun and are completely oblivious to the booming voice of John Bronson, the leader of the Army of the Unemployed, on the radio who is publicly pleading with the president to take action. This scene really hits home just how purposeless Judd intends to be as a leader. Shortly after, the carefree president is speeding in his car, trying to push it to 110 miles per hour, when he crashes it and loses consciousness.

Here's where the film takes a strange turn. While he's unconscious, divine intervention occurs. Penny is later convinced this divine intervention is angel Gabriel sent as a messenger from God to President Hammond. Suddenly, Judd Hammond is a changed man. He talks with purpose and actively seeks out meetings with the unemployed and racketeers. He wants to feed, clothe, and shelter the poor. He wants to punish the racketeers. This is all wonderful progress, for sure.

However, when Congress, the Senate, and the Cabinet all question him, the President requests the resignation of all the men who put him in power. Hammond then declares a state of emergency giving him full dictatorship. Hammond declares that he wants to be a dictator for the greater good, but I think most of us can agree that a man, without any checks and balances of any kind, who has sole power over a nation can be a very frightening prospect. In this film, Hammond is able to kill gangsters execution-style because he believes in an eye-for-an-eye. He bombs a ship to show how peace is needed in the world. Hammond certainly has the right ideals, but he gives himself such a position that denies citizens their right to a democracy. In the end, we see that an ailing President Hammond, a hero in the eyes of the public, has initiated the Washington Covenant, a signed treaty across nations, to ensure peace and prosperity for all.

As the film progresses, Franchot's character Beekman develops feelings for Penny and continues to idolize Hammond. When he appoints himself as dictator, Hammond changes Beekman's position of secretary to the President to secretary of war. It's not a large role for Franchot, but it has substance to it and he plays it well.

It's definitely an interesting treatment of politics in film. Because of its turn from democracy to dictatorship, this pre-code film is controversial to today's audience. Watching it, I grew uncomfortable when Hammond declared himself a dictator and obtained full control. Thankfully, he used his power for eventual good, but I was not in agreement with his ways of getting to that final peace agreement. I was astounded when Hammond ordered the execution of the racketeering gang and Beekman oversaw these orders. The scene played like one gang's retaliation on another gang, not a just and fair President's actions. Although I and many other current viewers have some reservations about the film's direction, audiences in 1933 loved the film's message. Desperate for a solution to the depression, hopeful about President Roosevelt, and eager for active change, Gabriel Over the White House was praised by viewers as an "inspiration" and "what the whole world is praying for."

Photoplay Magazine readers wrote letters praising the film.

Marshall Mills of Massachusetts wrote:

Walter Huston always comes through. It doesn't matter which kind of part he is asked to play, a hero or a villain, he is equally successful with either. In "Gabriel Over the White House" we enjoy him as a hero and a villain in the same picture. Nobody could be more the genial politician than the President Hammond we despised before the auto accident, and nobody more the patriotic statesman than the same character after his transformation. If there's a better actor in the business than Walter Huston, who is he?J.L. Norris of Washington, D.C. shared:

The people of this nation are truly indebted to Walter Huston. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, and the author for their work in putting "Gabriel Over the White House" before the public. It is the greatest and most dynamic hit of good propaganda ever put forth by any agency, including radio and newspapers. Incidentally, after seeing "Gabriel Over the White House" I had occasion to walk past the Executive Mansion on my way home. And somehow it did seem quite plausible that the Angel of Revelation has made his presence known to the head of our country.Alabama native E.B. Harrison, like many others, praised the actual President Roosevelt in his review:

After seeing "Gabriel Over the White House" I can truly say that it is the best picture I have seen in years. It not only shows the greatness of the actors and the director, but it gives the people of the United States a very good idea of the greatness of the man we have in our White House today.The New York Times reviewed:

Mr. Huston gives a vigorous and emphatic portrayal of Hammond. He reveals the man's weaknesses in the beginning and his vision and strength in the latter phases. He delivers the various speeches with vehemence...Franchot Tone is not especially impressive as Beekman and Karen Morley is only acceptable as Beekman's assistant...Gregory La Cava, the director, has handled the incidents in the Senate and in the open air with the desired imagination and forcefulness. The attack on the gangsters is set forth in a somewhat unbelievable and melodramatic manner, but the general effect of the meeting of the representative nations in the penultimate episode is depicted quite cleverly.In a more modern description of the film for its 1998 film series, the Library of Congress summarized:

The good news: he reduces unemployment, lifts the country out of the Depression, battles gangsters and Congress, and brings about world peace. The bad news: he's Mussolini. Gabriel Over the White House is a delight precisely because of its confused ideology. Depending on your perspective, it's a strident defense of democracy and the wisdom of the common man, a good argument for benevolent dictatorship, a prescient anticipation of the New Deal, a call for theocratic governance, and on and on.Gabriel Over the White House is available on DVD. Stay tuned for next Friday's continuation of the Franchot and Politics series!

Sources:

- Photoplay Magazine. June 1933; July 1933.

- Hall, Mordaunt. "Walter Huston as a President of the United States Who Proclaims Himself a Dictator." The New York Times. April 1, 1933.

- Library of Congress. http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/religion/films.html

Tuesday, October 4, 2016

Franchot Tone: Reserved Loner or Master Prankster?

|

| Franchot on They Gave Him a Gun set. Original photo from my collection. |

Franchot said about himself:

"But I never have liked to go around slapping people on the back and glad-handing them. I'm just not the type. For that reason I'd be the worst salesman in the world. I get my own enjoyment out of the quieter forms of entertainment and I feel silly and self-conscious when I try to whoop it up."Costar Spencer Tracy interjected:

"Don't let him kid you. He puts on that innocent, refined air to conceal the fact that he's really at the bottom of almost every practical joke that's pulled around here. Get him to tell you about the time he was kicked out of school for just that same sort of thing."Director W.S. Van Dyke added:

"Franchot Tone would make a perfect villain. He has that smooth, well-bred exterior which would let him masquerade as the perfect gentleman, while at the same time he would probably be pocketing the silverware, except for the fact that there isn't enough money in pocketing just silverware. We cast him as the heavy in 'They Gave Him a Gun' and he's showing up all the rest of the heavies in the business. That proves my point."Franchot grinned at Van Dyke's comment and explained further:

"I like to make friendships slowly and hang onto them. One of my theories of life is absolute sincerity and I don't seem to be able to dissemble my feelings and become somebody's old, old pal after I've known them for only about five minutes."When all of the other guys on set passed the time with card games, Franchot would wander off to the beach:

"Just because I'm not a nut on card games and I do get a lot of childish delight in poking around among the rocks and fishing shells out of the tidal pools and watching the sea anemones. Though I suppose that didn't help my reputation as a mixer, either."Spencer Tracy laughingly told a different story:

"What a line that guy can spin. What he was really doing down on the beach was coaxing an Irish setter to come up to the hotel so that he could hide him until after I'd gone to sleep and then push him into my room. I woke up about 3 a.m. and the darned dog was just like a muff around my neck. Nobody but that shy, reserved, retiring Mr. Tone could have pulled that one."Source:

"Franchot Tone No Back-Slapper But Those Who Work With Him Say He Plays Practical Jokes." The Evening Independent. April 1, 1937.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)