If one is to have a comeback film, I can't think of a better role or film. Directed by Otto Preminger and written by Wendell Mayes, the censor-breaking film was based on the popular and controversial novel of the same name by Allen Drury. You couldn't dream up a better cast: Lew Ayres is VP and Walter Pidgeon is senate majority leader, Henry Fonda as secretary of state nominee Robert Leffingwell, Charles Laughton as Senator Cooley, Don Murray as Senator Anderson, and Peter Lawford as Senator Smith. Gene Tierney and Meredith Burgess complete the cast in small, but effective roles.

With a runtime of over 2 hours, Advise & Consent is a twisting masterpiece that exposes the complicated relationships between and actions of honest and deceitful members of politics. For the purpose of this post, I am focusing on the treatment of the President and Franchot Tone's portrayal of that character.

As the film opens we see the headline "Leffingwell Picked for Secretary of State" boldly standing out on a newspaper front. This is not only news to the public, but to the senators who had agreed upon a list of suitable candidates for the position. None being Leffingwell, of course.

Senate majority leader Robert Munson (Walter Pidgeon) is on the phone to the president immediately. The president (Franchot Tone), calmly ingesting some pills with his morning coffee at his desk, explains that the former secretary of state has been dead for two weeks and the appointment cannot wait any longer.

"I had to get it done," the president states. When Munson questions his choice of Leffingwell who has "more enemies in congress than anyone in government," the president responds that he knows he's taken a risk, but that he thinks it will result in "creative statemanship."

"Maybe that's why I want him. He doesn't waste his time on trifles."

From the beginning of the film, we base our opinion on the fictional president (who is never given a surname, but later on in a single moment of the film is addressed as"Russ") on Munson's reactions. Playing the part of the trustworthy, morally-upstanding, and experienced leader, Pidgeon's Munson shows confidence when we should and likewise, expresses doubt when we begin to feel it. When Munson tells another senator that he will support the president all he can, the viewer feels that there's good reason. As Munson briefly pauses and adds "right now," we get a sense that there's an urgency to this support. Munson's reaction lets us know that perhaps this bold, party-splitting decision does not reflect the past actions of the president.

The president expects resistance, but does not foresee the total opposition from a cranky and plotting Senator Steve Cooley (Laughton) and straight-laced, firm Senator Brigham Anderson (Murray). When Cooley exposes communist ties in Leffingwell's past, Anderson heads the subcommittee in its investigation. In front of the committee, Leffingwell (Fonda) commits perjury.

When he reveals his perjury to the president and asks him to withdraw the nomination, the president is visibly stunned. In his role, Franchot's face freezes before he must sit back silently in his seat processing this confession. Realizing action must take place, the president, furiously smoking a cigarette, begins to pace the room. Leffingwell reveals that although he was never a member of the Communist party, he did attend some meetings out of curiosity as a young man. The president is silently pacing as he hears the explanation. The president never asks for more information. He simply asks, "Anybody else know you lied?" and when Leffingwell responds that one person knows the truth, the president with his back to the camera asks, "Will he talk?"

It's evident in the president's response that he's hoping to sweep the entire incident under the rug. Although a political loner, Leffingwell is consistently shown as a typically honest man who lies because he knows that any Communist association can ruin one's career. It is clear that Cooley has uncovered the one and only stain on Leffingwell's reputation. Still firmly believing in Leffingwell, the president refuses to withdraw his nomination. When that one person who knows Leffingwell lied does indeed talk, the president publicly shames Senators Cooley and Anderson in order to prove how strongly he supports his nominee.

Opening his speech in front of the White House Correspondents Association, the president astounds everyone when he goes off-script and declares that he will break the standard "No Reporters" rule and encourages reporters to get out their pencils and notepads. Smiling, the president, in highly undiplomatic form, then calls out his opposition Senators Cooley and Anderson. The president states:

This is your story...The President is standing by his nominee despite Senator Cooley's windstorm and Brigham Anderson's tunneling. You can tell your readers the president hasn't changed his mind about the nominee one fraction of an inch. He's going to fight for that confirmation no matter what.As he literally names Cooley and Anderson the collective Big Bad Wolf, the president sets up a narrative that Leffingwell is the innocent victim. Tone plays this scene with an interesting combination of playfulness and complete menace. He charmingly grins as he pretty much declares a personal war against the senators who disagree with him.

After the speech is over, a smiling and swaggering president meets with Anderson and Munson privately. Like a child who knows he's been naughty, but doesn't understand why he everyones taking it so hard, the president smirks at Senator Anderson, "Sore at me, Brigham?"

When Anderson responds that he's merely puzzled, the president confesses that he's angry that Anderson is holding up Leffingwell's confirmation when there are enough votes on the floor to pass him through. A man of principle, Anderson cannot endorse a candidate who lies under oath, and the following exchange occurs:

President: Aren't you interested in why he lied?

Anderson: I'm not completely unsympathetic. I just think that...

President: You think that he should let himself be ruined just because he flirted with Communism a long time ago?

Anderson: But the point is he should've told the committee that he had flirted with communism instead of lying about it on the stand.

President: Well, maybe there's nothing in your young life you'd like to conceal but we're not always that fortunate. We have to make the best of our mistakes. That's all Leffingwell has done. As the leader of our party, I'm asking you. Let me judge the man.

Anderson: Mr. President, I don't want to wreck his life. I don't want to deprive you of his services in some other office. But in this case, his confirmation as secretary of state, I am bound by my duty to my committee.

Anderson: Mr. President, I'm sorry, but your arguments won't wash with me.

President: My prestige is riding on this nomination. The prestige of this country, Senator Anderson. By God, that oughta wash. Or don't you know we're in trouble in the big world outside that little subcommittee of yours?

When Anderson replies that he will not back down, the president, infuriated, storms out of the room.

Again we, the viewers, look to the reliable Robert Munson to settle our feelings about the aggressive and insistent president we've just witnessed. Munson says:

I guess it is inconsistent, but I've come along way with him ever since we were green congressmen together. He's pulled us through 6 hard years of crisis. He's tired, Brig, and he's ill. I love the man. I guess I can stretch my responsibility a little, enough to help him.Munson's affirmation that the president hasn't always been such an unpliable leader, that this behavior is not common for him, and that he is unwell make the president a more sympathetic character.

Just minutes after we see the president make his remark that unlike Anderson, most people have actions in their youth that they'd like to keep secret, a blackmailer calls Anderson's home threatening to reveal a past indiscretion. Timing-wise, this couldn't be more perfect. This happens to Anderson directly after being publicly and privately attacked by the president of the United States. You cannot help but wonder whether the president, with his headstrong dedication to the nomination, could be responsible for something so under-handed. As I watched, I continued wondering whether a president, fictional or real, could get away with such a dirty play. *spoiler* Anderson is so desperate to keep a previous same-sex relationship quiet that he is driven to suicide. It's a devastating moment and I remember being stunned the first time I watched the film.

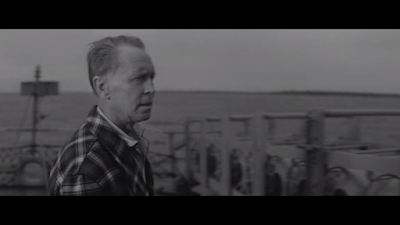

Vice President Harley Hudson and Robert Munson meet with the president on a dark dock to share the tragic news. Munson, again a kind of representative of the viewer throughout the film, must ask what we are all wondering. It's been discovered that a sleazy, manipulative senator Van Ackerman was behind the vicious blackmail of Anderson, but Munson can't help but add, "What I don't know is he alone in it. If he is alone in it, it becomes a senate matter, for the senate to handle in its own way."

The president asks, "And if Van Ackerman isn't alone?" before realizing that the suspicion is being cast on him. The president sees it in Munson and Hudson's eyes. Sees the doubt. Sees the fear. Sees the hurt. And we, in turn, see a genuine reaction from Tone's president. He lets his guard down to express raw disbelief:

Is that what they think of me on the Hill? Is that what you think of me, Bobby? As God as my witness, Harley, I know nothing.When Munson relaxes after witnessing the president's candid reaction, we know that we can stop wondering about it, too. When he warns that suspicion may arise if he immediately promotes Leffingwell, Tone's character responds:

The president is always suspect in some quarters because people are suspicious of power. Can't be chided by that. I'm sorry about Brig Anderson. Don't misunderstand me. I wish he were alive and happy. He's dead. Morning's coming and I still need a secretary of state. The situation hasn't changed except now you can bring Leffingwell to the floor for a vote. You've got the votes committed, Bobby. Use them.After he dismisses the Vice President (everyone dismisses the kind, disrespected VP throughout the film, but that's a post for another blogger to tackle), the president turns to Munson with an unexpected confession:

Bobby? I do want to confirm a suspicion to you. Maybe it'll help you understand why I want Leffingwell so badly... I'm going fast. Nothing left inside here that's working anymore. Leffingwell can take a firm grip on everything I've built up in foreign policy. Not let it all fall to pieces. Harley can't. You know he can't...I haven't any time to run a school for presidents! I haven't any time for anything. I guess I've been wrong in many, many things. I don't suppose history will have much good to say of me. I can't dwell on that. I've done my best.To this vulnerable intimation, Munson sincerely replies:

You're one of the great presidents, Russ.

The president's pending death is what is driving him to fill this position. He's desperate to continue his legacy, desperate not to lose any of the progress he's made in politics. He knows that Leffingwell is the man to continue the path and doesn't want to risk another man gaining the job.

Urgency is key to Franchot's part in this film. Although the film is lengthy and there are some segments of rather dry dialogue, there is a constant reminder that this decision needs to be made in a hurry. In the first scene featuring the president, he is telling Munson that he's announced the controversial nomination because he "had to get it done." The president wants Leffingwell because he "doesn't waste his time..." And in his final scene with Munson, the president uses a similar hurried vocabulary. Instead of saying, "I'm dying," Tone's character says, "I'm going fast...I haven't any time...I haven't any time for anything...I can't dwell on that."

The president knows he cannot dwell on the reputation he's gained since the Leffingwell announcement. He only knows that he must push the nomination through. It will be his final act as the leader of the country and he knows it. He's a powerful man and does not want to leave the future up to chance. He wants the secretary of state to be his decision, the final decision of his career.

I think you have to realize that this is a man who does not want to be remembered for dying in the middle of his second term. He wants to be remembered as a president who made progress in foreign relations and who paved the way for future progress with his appointment of Leffingwell. This is the last time for the president to define his legacy and make an active decision in power. He is all too aware of the disease conquering his body and he is desperate for one last stand. When you realize this as a viewer, I believe it softens the edges on the stubborn, aggressive politician we see at the correspondents' speech and in the private meeting with Senator Anderson. The urgency to fulfill this last act before leaving his legacy up to the history books is what drives Franchot's president to take such an unorthodox approach. Franchot's president is not a revered leader, but a flesh-and-bone, flawed human being.

*spoiler*Despite all of his efforts and the tragic event that occurs, the president is not able to secure the vote in time. We hear but do not see the president collapse, before the voting on the floor is complete. The eternally put-upon and doubted Harley Hudson, making a bold move as the new president, halts proceedings so that he can choose his own secretary of state.

The Novel

I have not read the original Advise & Consent novel on which the movie was based. However, from what I've read about the book, the president within its pages is implicated in the blackmail scheme. In the book, apparently the president supplies Van Ackerman a damning photo of Anderson. It is explained that the president doesn't think that Van Ackerman will actually use it and does not expect Anderson's reaction to it. None of this happens in the film version unless we are being unknowingly led, by the president's convincing denial and Munson's steadfast support, to believe differently. (Although I did think the first call to Anderson's house sounded a bit like Franchot's gravelly voice, so you can sleuth it out and see if I've completely been duped by the fictional president and his friend Bobby Munson!)Response to the Film

Preminger designed a 20-second color theatrical trailer for Advise & Consent to be shown at screenings of his film Exodus. According to Box Office Magazine, pre-production work had just begun so this was the first instance of a theatrical trailer being released far in advance of a release date.Here is the official 4 minute-long trailer with a behind-the-scenes look. (If the embedded video doesn't play, click here.)

Film Bulletin called Advise & Consent a film of distinction. It noted that the film would:

anger some, please others, intrigue all. It has been unfolded in an intelligent, informative, and engrossing manner, and thanks to Preminger's skill as a film maker, the bold aspects have been presented with good taste and reasonable consideration of the national welfare...What makes 'Advise and Consent' so noteworthy is that its solid dramatic merits actually overshadow the many controversial aspects. Movies dealing with political life usually have leaned toward the bizarre and bombastic. This does not. It has a quality of seeming factuality and dramatic validity.The Bulletin singled out Franchot's lifelong friends Charles Laughton and Burgess Meredith for their performances and noted that Franchot gave a "fine delination" as the "strong-willed, seriously ill President."

Never very kind to Tone as a general rule, New York Times reviewer Bosley Crowther reviewed the "sassy, stinging" film this way:

Mr. Preminger and Wendell Mayes, his writer, taking their cue from Mr. Drury's book, have loaded their drama with rascals to show the types in Washington. Their intense and deliberate projection of a cynical attitude toward the actions of politicians extends right up to the President of the United States, whom they frankly portray in this fiction as a man of peculiar principles. He is made (in a tasteless portrayal of a sick, testy man by Franchot Tone) to be tolerant of cheap conniving and the telling of lies under oath.Weeks ago, I was researching this topic in old magazine and newspaper articles, and I came across a mention of Franchot's pride in the film. The article said that Franchot was so proud of Advise & Consent that he flew in his two sons to an early screening of it. Unfortunately, I was in a hurry and didn't save the article. I've tried duplicating my search, but no luck so far.

Thank you for checking out my take on Franchot's U.S. President in Advise & Consent. Please head over to Pop Culture Reverie to read other great posts in the Hail-to-the-Chief Blogathon.

Next up in my own Franchot & Politics series, I'll be covering the 1936 political film The Gorgeous Hussy. Additional posts I've written in my Franchot & Politics series include:

Sources:

"20-Second Trailer Ready on Preminger's 'Advise'." Box Office. August 7, 1961. 17.

"'Advise & Consent' Provocative, Controversial and Good Drama." Film Bulletin. May 28, 1962. 11. "Screen: 'Advise and Consent' Opens:Movie on Washington Is at Two Theatres." The New York Times. June 7, 1962.

No comments:

Post a Comment